Switching from a Mac to a Chromebook (as a web developer)

This is my experience switching from a 2014 Retina Macbook Pro to a Google Pixelbook. Doing this is by no means for everyone, but I wanted to share my findings for anyone toying with the idea.

Edit as of June 6th, 2018: I’ve experimented with two more ways of getting a development workflow on my Pixelbook and have updated the post to reflect them below.

Background

Ever since Apple announced their unibody aluminum MacBooks in 2008, I‘ve been a huge fan of the Mac.

Their attention to detail and tightly coupled hardware and software immediately wooed me into buying into their ecosystem. It was a blast into the future, especially considering I started off with roots in Windows 2000, Notepad++, and IE6.

The Mac introduced me to Unix, its sophisticated build tools, and the command line. I got spoiled by software like Homebrew, Sketch, and Pixelmator. As the years went by, I’ve always thought it was obvious that the Mac was the best platform for developers like me.

Today, that’s not the case.

To be clear, this post isn’t about bashing Apple. If someone were to ask me what computer they should buy if they wanted to get into development, I’d likely recommend a MacBook Pro.

This is more about my waning faith in the Apple ecosystem.

Something has been off since Steve Jobs’ untimely death. With the release of plastic iPhones, iPads with pens, and MacBooks with touchbars, I’ve been feeling Apple’s been steering further away from the original vision of all their products.

Product refreshes have been underwhelming to say the least, and their recent, seemingly poor design decisions on products such as the Magic Mouse — a device you can’t use as it charges — have really made me start looking elsewhere for an experience that just works.

Enter Google

Google has been competing with Apple for a while now, with the likes of Android, Google Apps, and Chrome. Their products are by no means perfect, but whether we like to admit it or not, a lot of us have already sold our souls to many of them. e.g. Gmail is the de facto standard for email and Google Docs is a go-to for any type of document collaboration.

This was the primary reason I switched from iOS to Android 3 years ago, and it’s one of the few reasons why I’m picking Chrome OS over macOS today.

![]()

Just this past October, Google announced the Pixelbook, a gorgeously made machine with top-notch specs, tablet and laptop modes, and a Wacom-powered pen. This was the first computer that got me to the same level of excitement as the unibody MacBook since 2008.

This got me seriously considering, what would happen if I replaced my MacBook Pro with a Pixelbook?

So I ended up ordering one.

Workflow

Email, calendar, word processing, spreadsheets, presentations, reminders, notes, and 95% of all my non-dev needs have been handled ubiquitously by Google Apps for years, so that was off my radar (not to mention the Pixelbook supports running Android apps).

I was really only concerned with two things: design software and development environment.

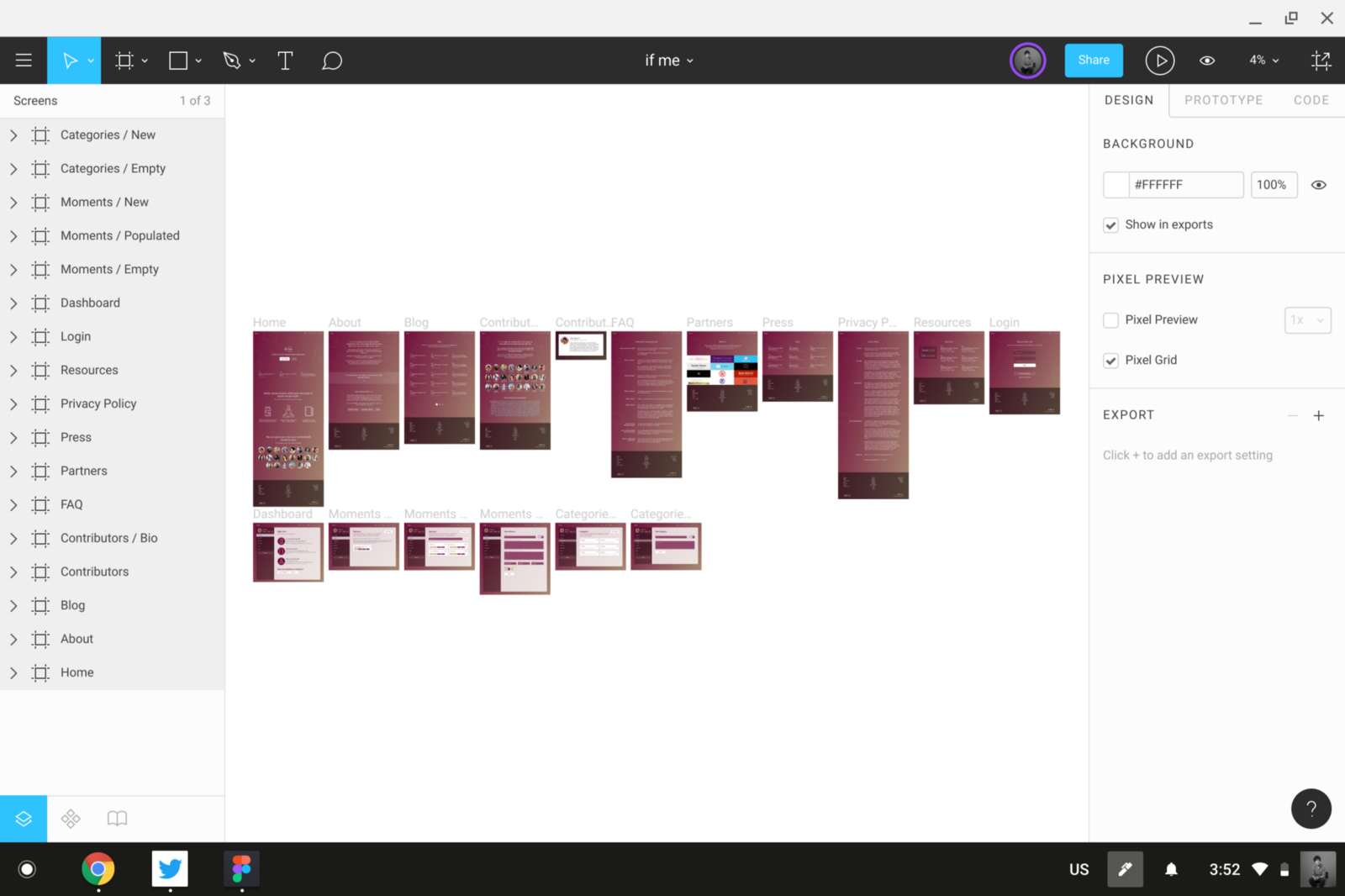

Turns out Figma is an excellent web-based design tool — its toolset closely mirrors Sketch with a few minor differences. After spending a couple weeks exclusively using Figma, I determined that I could live without Sketch and Pixelmator on the desktop.

The harder problem was development environment.

Again, turns out there are several options, though in the end I found only one to be completely satisfactory.

The first option I explored was using cloud IDEs. There are a handful of them out there: Cloud9 IDE, Codeanywhere, Codenvy, CodeTasty, and a few more. After trying all of them, I found Cloud9 to be the most robust and not-janky feeling IDE.

I tested Cloud9 by using the free tier exclusively for a pull request on a volunteer project using a Rails & React.js stack. My main gripes with Cloud9 were:

- I had to implement a lot of workarounds in my development flow. Servers wouldn’t run without specifying

$C9_HOSTNAMEeverywhere, PostgreSQL databases on Cloud9 didn’t support unicode by default, and only ports 8080, 8081, and 8082 were open. - It’s not very customizable. It ships with a classic and flat theme, but both pale in comparison to modern editors like Visual Studio Code or Atom.

- Its future seemed unclear. It recently got acquired by Amazon, its favicon is still not Retina-ready in 2017, and its blog is not very active.

Although I could live with these issues, I didn’t want to have to sacrifice my development experience just so I could own a new and shiny Pixelbook.

There were a lot of great things about Cloud9 though, such as: autocompletion support, built-in terminal, robust keyboard shortcuts, and good syntax highlighting.

The second option was to install Termux and use a local Linux server without putting my computer in developer mode (here’s an excellent guide written by Kenneth White).

This had a lot of promise, but I ran into a one gamebreaker gripe: I didn’t have sudo access. This is just plain necessary for certain things. I tried installing a couple packages I regularly used but got blocked by permissions errors. I may revisit this again in the future, but I shelved this option for now.

The third option was to setup a VPS, and this is what I'm sticking to as I write this. This seems like the correct option as a Chromebook user — to put my faith in the cloud and commit to using the cloud for all my computing needs.

Now, I could have put the Pixelbook in developer mode, installed Crouton, and run Linux from the device natively, but I didn’t want to deal with hardware incompatibility, losing Google Assistant, and making my device way less secure.

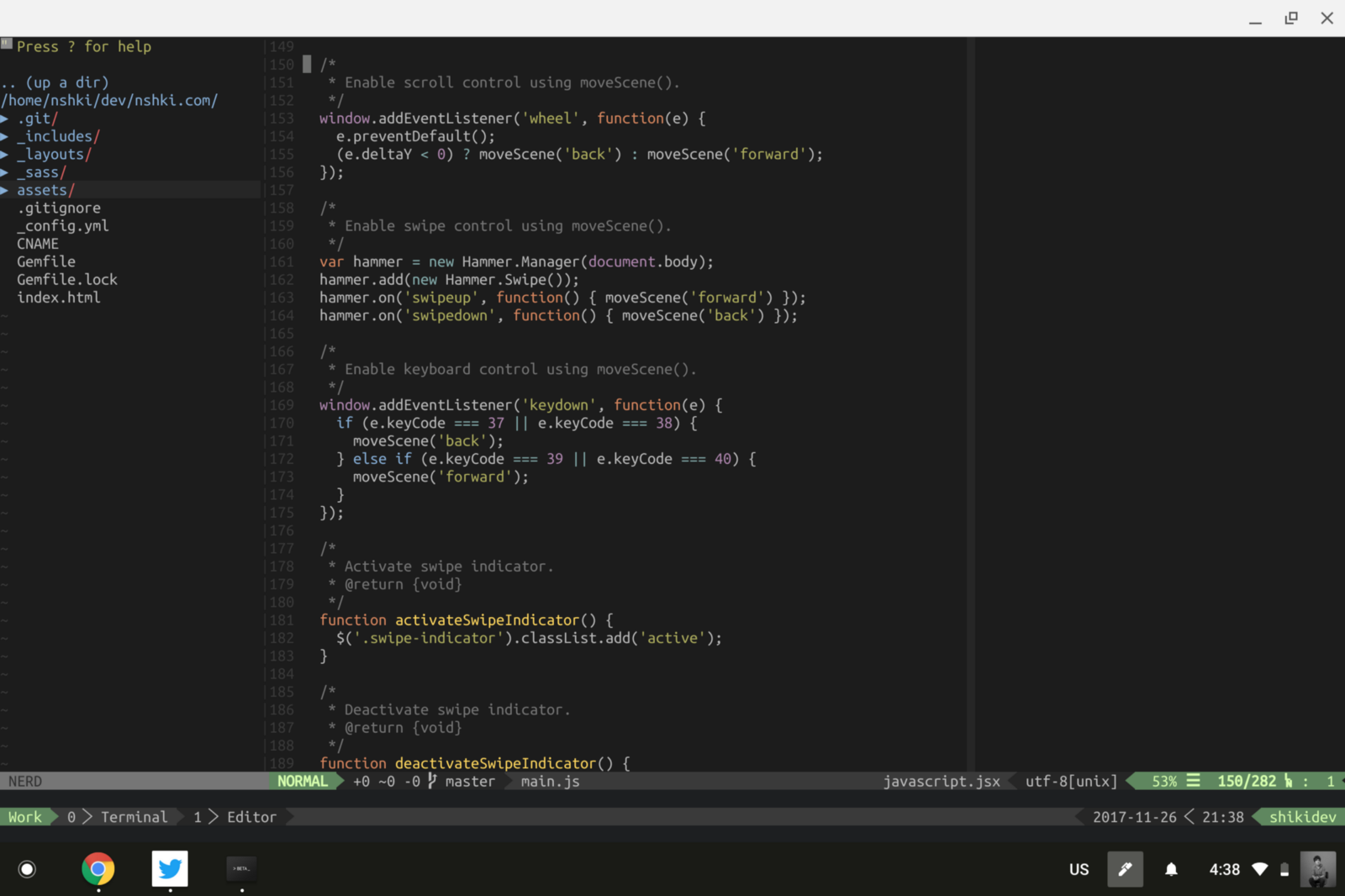

Instead, I setup a DigitalOcean droplet with a fresh install of Ubuntu 16.04, and everything worked as it should with none of the gripes listed above.

For my editor, I went all-in with Vim and have been very pleased. Thoughtbot’s write-ups and videos on Vim have been incredibly great resources.

Fast forward several months. The fourth option is giving in and using Crouton to run a Linux distro alongside Chrome OS.

Some time after publishing this article initially, I decided to finally give Crouton a try. Like I mentioned above, I expected a few cons to this approach: hardware incompatibilities, losing Google Assistant, and having a significantly less secure machine. I was in for a bit of a surprise.

There were reports of a faulty trackpad online, but I didn’t experience that at all with a local install of Ubuntu. The top row of the Pixelbook keyboard — with the exception of the escape key — unfortunately did not work, but I was able to make due.

The installation process itself was quite straightforward. I ended up using Ubuntu’s guide on installing Linux on a Chromebook, and was able to smoothly set the machine up with no problems. Enabling developer mode was a bit scary since you end up facing an intimidating screen about OS verification being off on each boot, but as long as I didn’t press the space bar which would completely wipe the machine, I was good.

Ubuntu works like...Ubuntu. There were no particularly unique snags. I quickly installed all my developer tools and configured an environment just as I would have on a Mac. You can even seamlessly switch between Chrome OS and Ubuntu by using the keyboard shortcut Ctrl+Alt+Shift+Back, which meant I didn’t lose Google Assistant or any other Chrome OS feature after all.

From a day-to-day standpoint, I believe that Crouton makes Chromebooks a completely viable option for developers. Though I’m not a security expert, many others online warn of having developer mode on as a security risk, so use this option with that in mind.

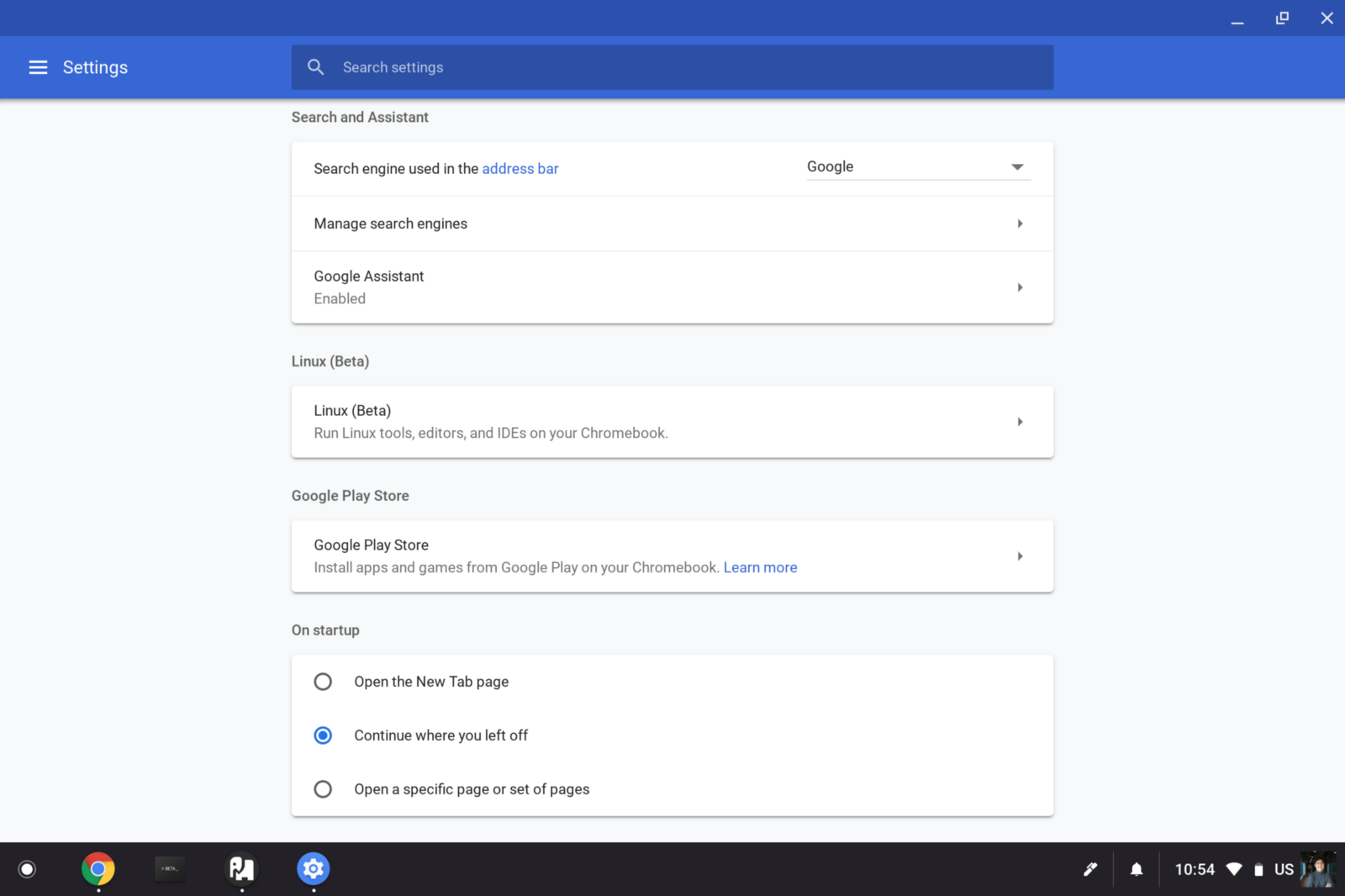

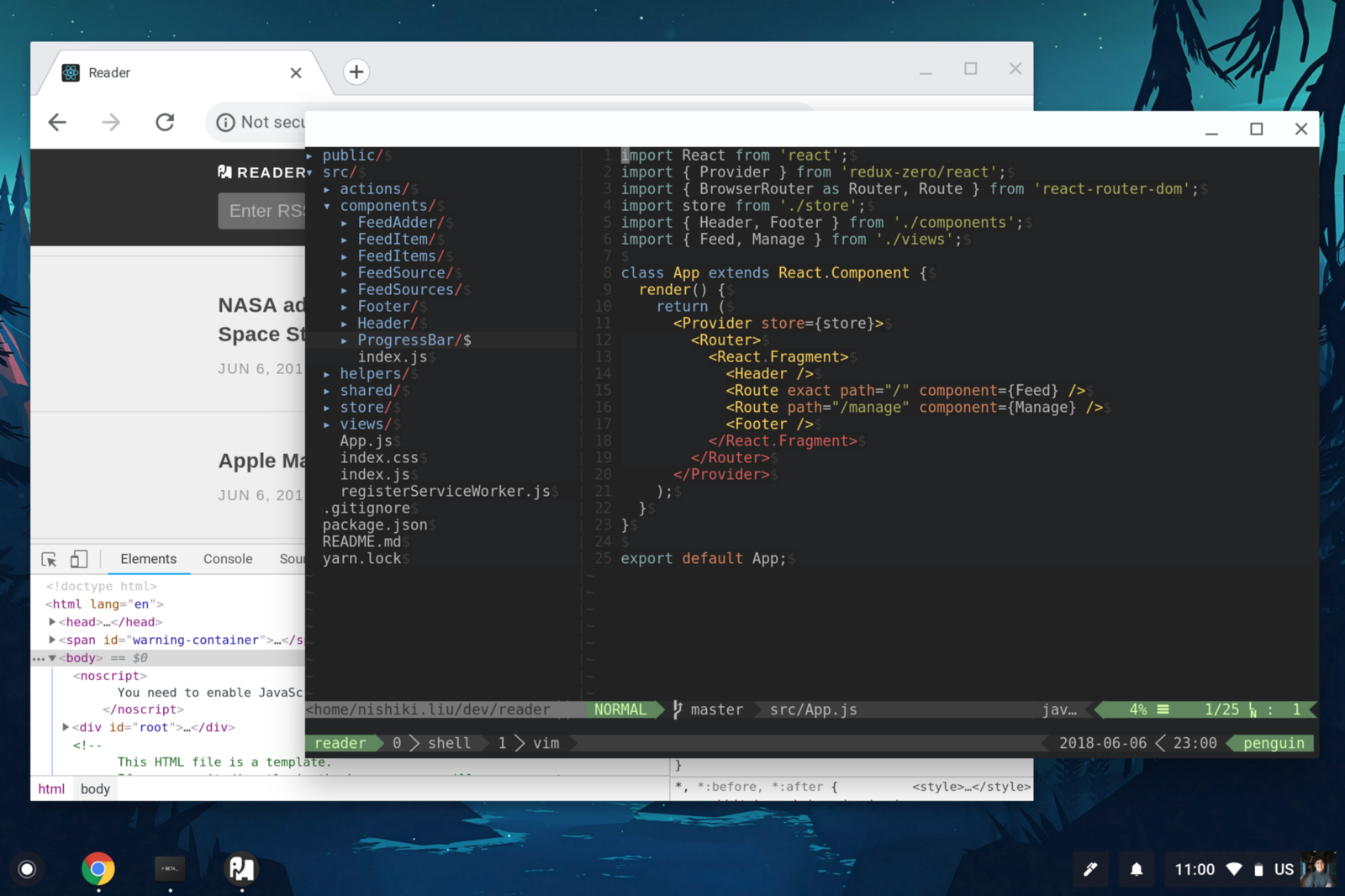

The fifth and most recently possible option is to use Chrome OS’s new Linux Apps feature, also known as Crostini.

At Google I/O 2018, Google announced being able to now run a Linux VM within Chrome OS. I heard some tid bits of this on the Crostini subreddit before this was officially announced, and have been completely on board with this since.

This feature is still under active development, but the Pixelbook (and a few other machines) can switch to the Chrome OS dev channel to begin using Linux apps now.

EDIT (September 26, 2018): Linux Apps are now available on the stable channel for Chrome OS, so this should be enable-able out of the box!

This takes the cake for me for my Chrome OS development setup. This is similar to having a Termux setup, except that the Linux environment allows sudo and is natively supported by the Chrome OS team. Furthermore, you don’t need developer mode enabled, so you get all your security and peace of mind back.

Since Linux is running in a VM, accessing web apps requires you to use the VM’s IP address or simply just As of stable versions of Chrome OS in early 2019, accessing penguin.linux.test, which is more convenient.localhost now works as expected.

So far, I’ve run into no issues with my development environment or command line tools. I’m quite a happy camper.

Closing Thoughts

I’ve been really happy with my Pixelbook so far. I was able to consolidate my devices and put my money towards an ecosystem that I believe is only going to get better.

Some might ask, why not the Surface? To be honest, I seriously considered the Surface Book as well. I used exclusively Windows via Bootcamp for a week to get a hang for the new Linux subsystem, but kind of like the Cloud9 trial, there were too many hoops to jump through to get an ideal development environment.