Vim, one year in

I started exclusively using Vim as my editor a little over a year ago.

This wasn't a decision I made lightly. I was heavily invested in the Atom editor ecosystem at the time, but was also transitioning into using a Chromebook as my primary machine. Linux apps support was not yet released, so I experimented with multiple ways of viably programming on Chrome OS.

I eventually committed to using Vim since it was an editor that is supported on virtually any environment. At the time, I figured I could program on a VPS on a Chromebook to stay true to having literally everything in the cloud. I was also always intrigued by Vim since I've read that it's a skill that you can develop over time, and productivity gets a huge boost as a result.

As a fallback, if I hated it, I could just run Ubuntu on my Chromebook and go back to my old ways.

Turns out I didn't hate one bit of it.

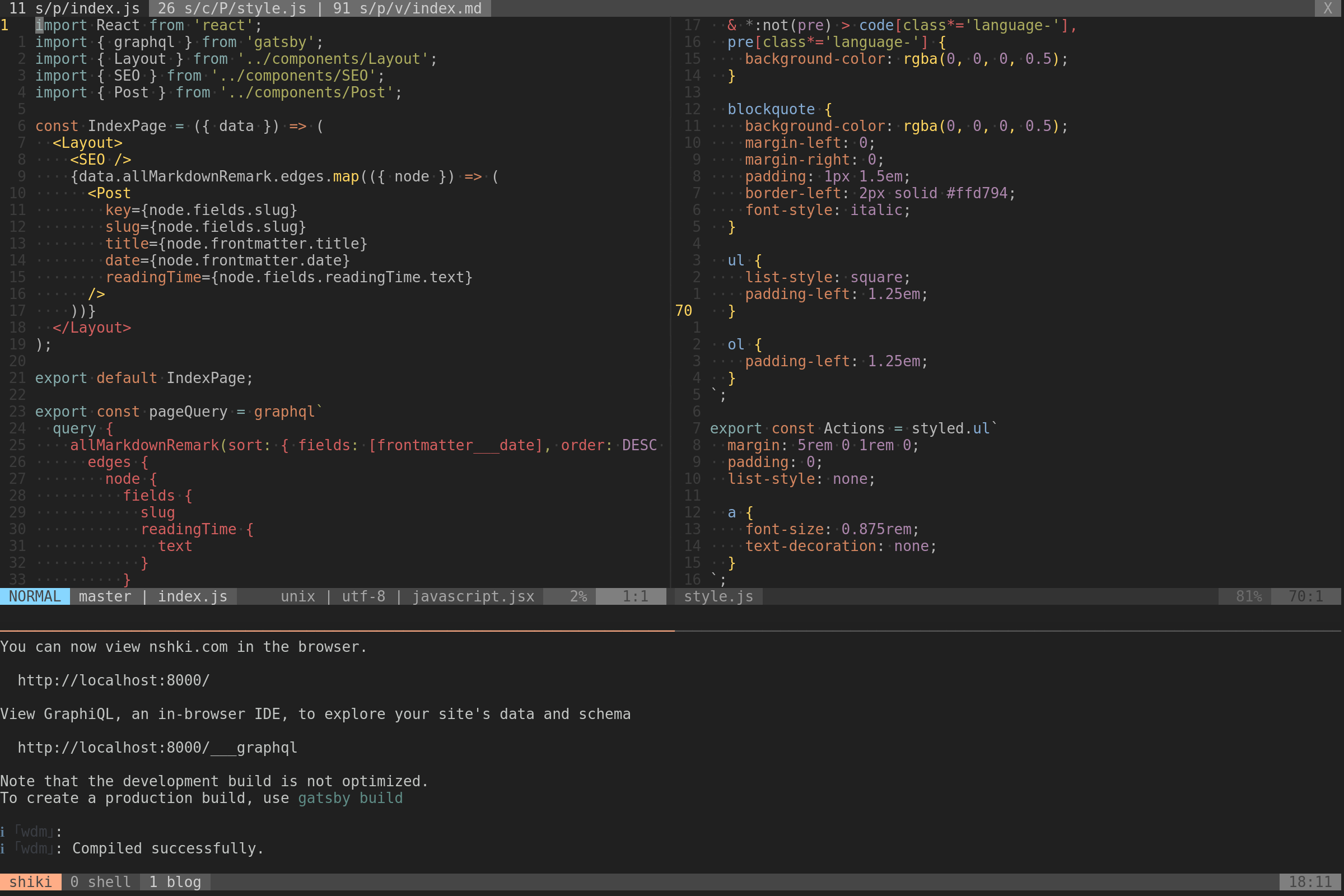

Shown here is what my current Vim setup looks like. It's technically Neovim, but I still count it as Vim, and I have Tmux in the mix as well.

I type around 120 WPM. When I have to stop and move a mouse, it really breaks my flow. It took me a couple days to get used to awkwardly navigating around with only my keyboard, but once I got somewhat of a grasp on that, I could already tell I'd be able to work faster than before.

What really got me, though, was when I discovered how to change everything within parantheses. With the help of a few keystrokes -- ci( -- I was able to change something like this:

best_flavor(ice_cream: 'chocolate chip cookie dough ice cream', bubble_tea: 'taro lychee fancy schmancy stuff')

...to this:

best_flavor(everything: 'vanilla')

Like everyone else, I was intimidated by what I thought were mountains of keyboard shortcuts to start using Vim even half effectively. To my surprise though, they really weren't that hard to remember at all.

Most key combinations in Vim are mnemonic. Take ci( from earlier as an example, it literally reads as "change in ()". Even the keys used to navigate correspond to English words, such as w for word and b for back. Vim commands really are like you're talking to your editor, and that makes it fun to use.

As far as functionality goes, I just had to spend a little time finessing my config and I had everything that I had in Atom and more. Vim has an incredibly rich plugin ecosystem, and the minor tweaks needed to make it look more like a modern editor were very easy. My .vimrc is open sourced on GitHub if you're curious!

The one bit that took me a while to fully comprehend was the concept of buffers. I've always seen Vim screenshots with multiple files open so I assumed it had tabs just like any other program.

Buffers are in memory. You can have the contents of a file loaded in it or it can be a blank slate. Each Vim session has one buffer per file you have open. This means that you can have multiple panes in Vim looking at the same file (this is useful for things like referencing sections of a file while you write in another section). You can cycle through buffers in any given pane.

Vim tabs, on the other hand, are just ways to organize panes. If I want a two column vertical split as one tab and a three row horizontal split in another, I can do that, and I can flip between them whenever.

Once I got that, I was much more comfortable in Vim land. Thanks to my friend Justin for constantly hounding me about using buffers.

Overall, I don't regret my decision to switch to Vim one bit. It feels liberating, and it's amazing to invest time in a tried-and-true piece of software that's just as old as I am.

Nowadays, I only have three apps open on my computer: a browser, Slack, and a terminal. If I ever need to SSH into servers to edit anything, I usually have my favorite editor available to me right on the server. To top it off, I work faster and more efficiently than before without a mouse slowing me down.

If anything changes, I'm sure I'll write about it, but I don't see that happening anytime soon.